In this age, when highways crisscross most of the land, a truly off-the-grid adventure is difficult to come by. Eugene resident Bob DenOuden reflects here on an off-the-grid visit to the Owyhee Canyonlands last spring and why the Owyhee is meaningful to him.

Bob DenOuden takes a break on a canyon rim in the Owyhee.

In this country, at least outside of Alaska, we have grown accustomed to the idea that there is nothing left to be explored. Most of us believe that every nook and cranny has been visited; everything interesting has been discovered, mapped, photographed and posted on the Web.Oregon is certainly no exception to this impression. With less than 4 percent of our state protected as federal wilderness and laced by more than 200,000 miles of road, Oregon is a fragmented state where it can be difficult to find true adventure. But if one pulls out a detailed map and looks closely at the southeastern corner, there are intriguing discoveries to be made.

Over the past few years, pal Alan Butler and I have made a point of seeking out some of these tempting blank spots on the map at least once a year, usually in late spring. For our trip last year, we settled on a little-known side canyon of the West Little Owyhee River in the Owyhee Canyonlands: Toppin Creek Canyon.

In May, we set out on our adventure. It is quite a drive from Eugene, where we both live, to the starting point for our planned four-day trip; over 450 miles – and the last 60-plus are unpaved and increasingly rough as you go. We broke up the journey with an overnight stop in Bend and were on the road again before 6 the next morning.

The route through Burns and on to Burns Junction is now very familiar to us. We decided it would be well advised to begin the trip with a full tank of gas, so we continued on to McDermitt, Nevada, for a gas stop. Backtracking about 10 miles on Highway 95, we left pavement and headed east for Anderson Crossing on the West Little Owyhee River.

This ford is somewhat of a fabled spot on our mental maps, having heard from others about the grandeur of the West Little. We lingered a bit, both to make sure the river was safe to cross as well as to soak in the quiet beauty of the river here. It is still a long way from Anderson Crossing to our starting point at the head of Toppin Creek Canyon, and we were not sure it would be passable due to recent thunderstorms that had turned sections of the road into that familiar eastern Oregon gumbo mud. Alan gunned his engine as we surfed through a few particularly bad spots and soon we were committed – no turning back now. It was late afternoon when our GPS told us we were in the right spot to park the rig and head out on foot.

Three years ago we had planned a similar side canyon exploration, this time down Big Antelope Creek, which flows into the main Owyhee River just above Three Forks. For that trip, we had very high water as well as unrealistic expectations of how difficult the terrain would be. While we saw incredible things in Big Antelope, as well as along the rim, these trip-planning failures – along with a quick moving storm roaring in out of the southeast – caused us to change plans and quickly scramble out of the canyon.

This trip had none of the high water issues from the last two springs – in fact quite the opposite. Most of Oregon had been bone dry last year, and this was especially true in the southeastern corner, recent rains notwithstanding. We packed in about 2 gallons of water each and hoped we would find available water in the canyon. The first 2 miles were dry, and we began to think about Plan B, but soon we arrived at a beautiful pour-off with a pool at its base 40 feet below. We had to scramble out of the canyon and back down to reach it, but it was doable and soon we were on our way, deeper into the canyon.

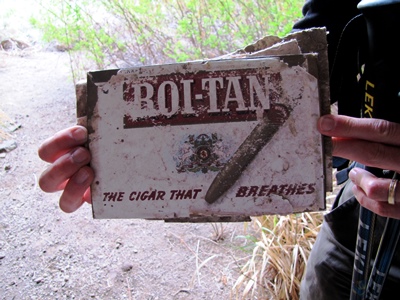

One of the great things about Toppin Canyon, and the many other side canyons of the Owyhee River system, is that while exploring them it is very easy to imagine that you are the first person to have visited for a very long time. We saw no human footprints and, except for an old Olympia beer can from the 1970s and an even older cigar box stuffed in a recess in one of the many caves and overhangs we explored, there were no human artifacts or trash to be seen.

One thing we did see were hundreds of beautifully crafted cliff swallow nests lining the canyon walls. At times, particularly in the morning, hiking in Toppin Canyon was like walking through an aviary. By early evening of the first day, we climbed out of Toppin Canyon and found a campsite with a great view on the canyon rim. As we enjoyed the lingering sunset and a chorus of coyote song, we looked forward to the discoveries we would encounter the next day.

One thing we did see were hundreds of beautifully crafted cliff swallow nests lining the canyon walls. At times, particularly in the morning, hiking in Toppin Canyon was like walking through an aviary. By early evening of the first day, we climbed out of Toppin Canyon and found a campsite with a great view on the canyon rim. As we enjoyed the lingering sunset and a chorus of coyote song, we looked forward to the discoveries we would encounter the next day.

According to our plans, by the end of the second day we we would either make it all the way to the confluence of Toppin Creek and the West Little Owyhee or we would have to change course, as there would not be enough time to spend another night in the canyon. Soon, the walls became higher and steeper and the canyon bottom became narrower and rockier. By midday, we were forced to skirt deep pools of standing water and crash through thickets of dense and thorny shrub. As difficult as the going got, the promise of a new discovery around every corner made it impossible to turn back.

According to our plans, by the end of the second day we we would either make it all the way to the confluence of Toppin Creek and the West Little Owyhee or we would have to change course, as there would not be enough time to spend another night in the canyon. Soon, the walls became higher and steeper and the canyon bottom became narrower and rockier. By midday, we were forced to skirt deep pools of standing water and crash through thickets of dense and thorny shrub. As difficult as the going got, the promise of a new discovery around every corner made it impossible to turn back.

The going became very slow, and by late afternoon we had to face the fact that we did not have enough time to keep moving forward at the bottom of the canyon. Laboriously, packs still weighed down by gallons of water, food and gear, we made our way up the canyon wall, trying to find a way to the rim. A major goal of the trip had been to visit the point of land where Toppin and West Little Owyhee canyons meet, called the Toppin V. We estimated the Toppin Creek Canyon to be about 600 feet deep where we attempted to exit up on a promising scree slope leading to what appeared to be a gap in the final course of rimrock. What we found there, however, was another course of vertical rock above completely blocking our route. Exhausted and a bit frustrated, we attempted to skirt this obstacle by traversing a steep section of scree around a blind corner where we hoped to find a way up. We were lucky and located a passable route up to the rim, where we rested and enjoyed a fabulous view back down into the canyon we had just explored.

The going became very slow, and by late afternoon we had to face the fact that we did not have enough time to keep moving forward at the bottom of the canyon. Laboriously, packs still weighed down by gallons of water, food and gear, we made our way up the canyon wall, trying to find a way to the rim. A major goal of the trip had been to visit the point of land where Toppin and West Little Owyhee canyons meet, called the Toppin V. We estimated the Toppin Creek Canyon to be about 600 feet deep where we attempted to exit up on a promising scree slope leading to what appeared to be a gap in the final course of rimrock. What we found there, however, was another course of vertical rock above completely blocking our route. Exhausted and a bit frustrated, we attempted to skirt this obstacle by traversing a steep section of scree around a blind corner where we hoped to find a way up. We were lucky and located a passable route up to the rim, where we rested and enjoyed a fabulous view back down into the canyon we had just explored.

From there the Toppin V was visible and an hour later we were setting up our tent at what is among the premier campsites in the Owyhee Canyonlands, if not the entire state of Oregon. As tired as we were, it was not possible to sit and relax; there was simply too much to see. Below us was a wonderland of rock spires jutting hundreds of feet from canyon bottoms. The impossibly complex rock walls reminded me of southern Utah’s Cedar Breaks or Bryce Canyon formations. We stared for hours, trying to see everything at once and taking photos we knew would never do the place justice. The next morning gave us more opportunities to study in amazement the canyons all around us in a different light. Reluctantly, we had to turn away from these vistas and begin the walk back to the truck.

After returning to our truck we spent one more night in the Owyhee Canyonlands, this time on the west rim of the main Owyhee River just east of Toppin Canyon. As night came and the stars came out, we sat at the edge of this 1,000-foot-deep chasm, looking across toward Idaho and reflecting on what we had seen. Each trip we take into this corner of Oregon leads to more discoveries, which beget future trips. The best discovery, however, is that there is, indeed, real adventure to be found in Oregon after all.